[ENGLISH BELOW]

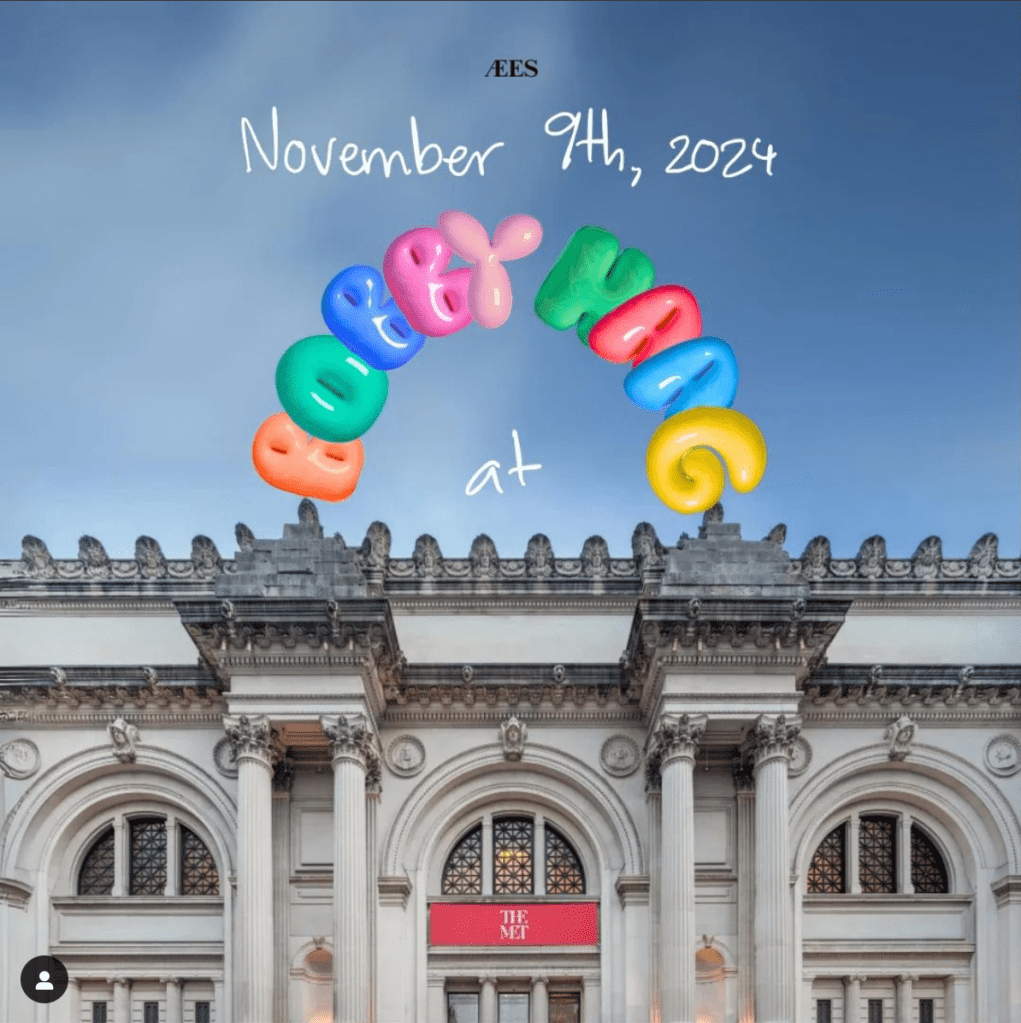

Bobby Haag en el MET

La crítica: un gesto necesario, siempre urgente, que hay que renovar constantemente. Es una forma de mirar mejor lo que vemos, de conocer mejor nuestros propios deseos, de alzarnos contra lo que, como se suele decir, «ya hemos visto demasiado». Y para imaginar mejor las posibilidades emancipadoras de los tiempos venideros.

Georges Didi-Huberman

Conocí a Ignacio Neri en el contexto de la organización del evento Imaginación política: encuentro internacional, llevado a cabo en febrero de 2017 en el MUAC. Él nos apoyó para pagar la traducción inglés-español y viceversa, de todo el evento. Le dejé de ver hasta la presentación del libro Adiós al arte contemporáneo, ¡viva el arte anacrónico! en Biquini Wax. Compró el libro (insistiendo en pagar por él) y unas semanas después me contactó para comunicarme lo inspirador que le había resultado. Jamás me lo imaginé. Hace poco de nuevo me escribió para contarme de un plan que ha ideado junto con el artista Bobby Haag a llevarse a cabo el sábado 9 de noviembre en el Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) de Nueva York. En este texto contaré un poco acerca de esta confabulación suscitada por conexiones inimaginables.

Neri es originario de Tulancingo, Hidalgo, estudió en el ITAM y después comenzó a coleccionar y promover como galerista a artistas de espacios auto-gestionados como Biquini Wax y Cráter invertido, entre otros. Hace 3 años se fue a estudiar a Nueva York una Maestría en Ciencias del Cambio Climático, en Columbia. Desde ese entonces vive y trabaja en esa ciudad. Me comenta que ha visitado gran cantidad de exposiciones y eventos de arte y que está seguro de que se produce mejor arte en la Ciudad de México que en Nueva York. Sin poder dar cuenta del porqué exactamente, compartimos una idea –profundamente sentida y comprometidamente romantizada– de que por alguna razón los contextos adversos y tiempos de peligro incitan la creatividad, o al menos así se vive cuando estás ahí.

Por su parte, Haag es un artista que pinta al óleo desde los 20 años. Pintó toda una década solo y para sí mismo, sin mostrar sus pinturas al público. Luego en mayo de 2022 se mudó a Nueva York, a Brooklyn, en Bushwick, un barrio que está en proceso de gentrificación. La primer pintura que hizo en esa ciudad fue un retrato de la persona que le dijo “sigue tus sueños”. Ese cuadro es particularmente interesante porque a diferencia de otros de sus trabajos, en esa figura hay una gran cantidad de colores mezclados configurando texturas que por momentos parece que son totalmente aleatorias y por momentos parecen estar perfectamente calculadas. En esa obra Bobby parece depositar todos sus afectos por ese personaje volviéndole algo ficcional, como un ser etéreo que, en todo caso muy probablemente tiene más que ver con su propia forma de responder ante esa sugerencia que con el sujeto en sí mismo.

Ya en su estancia como neoyorkino, comenzó a trabajar como parte del equipo técnico de la casa de subastas Christie’s. Pero paralelamente comenzó a pintar las cosas que veía en Central Park, cerca del MET, pues ahí encontró una serie de escenas que le inspiraban a ser plasmadas en óleo. A partir de ello decidió exponer una de esas pinturas ahí mismo, en el parque, por un día entero, de 6am a 6pm, seleccionada para ser mostrada solamente en una ocasión por cada estación del año, es decir, una cada 3 meses aproximadamente. Valga la mención de este anacronismo que puede remontarnos tanto a aquellos gestos decimonónicos del intento de escapar de los imaginarios urbanos para dejarse arrobar por aquello que en aquel momento todavía se idealizaba como “naturaleza”, como a motivos de inspiración más clásicos todavía que se pueden encontrar en gran cantidad de pinturas, esculturas, música, etc.

Del 9 al 15 de agosto de este año, Haag tuvo la oportunidad de participar en la exhibición y subasta “Christie’s Inside Job”, organizada por la renombrada empresa que como muestra de generosidad permite a algunxs de sus trabajadorxs. Ahí hizo su primera y única venta de obra hasta el momento. Mientras tanto, continuaba con su actividad en el parque. Las pinturas de Bobby son por lo general un tanto toscas. Y él mismo admite su falta de maestría técnica. Dice: “si alguna de mis pinturas remiten a alguna corriente artística o a la obra de algún otro artista hecha antes es simplemente por falta de dominio”. Colores disímiles y en ocasiones vibrantes se emplastan a tal grado que generan texturas tanto táctiles como visuales. No podemos decir, y con certeza él mismo no podría demostrarlo, hasta qué punto este efecto es voluntario. Por momentos parece tan infantil su trazo que bien podría ser resultado de un esfuerzo por permanecer naif. Sólo lxs policías de la consciencia irían tras esa pesquisa. Si ello carece de importancia no es solamente porque en sí mismo el acto de pintar ya fue sobreexplotado por los circuitos del supuesto saber sobre el arte, sino porque, aunque siga y seguirá siendo un pretexto para volcarse sobre cualquier superficie y devenir imagen, el gesto crítico no está solamente ahí. Está en lo que hacemos con ella.

Para Neri, el arte de Haag le recuerda al de Henri Rousseau, sobre todo en cuanto a la factura y el modo autodidacta. Pero al mismo tiempo, Neri también vio en él algo de David Hammons, en el sentido de salir a la calle y hacer una exhibición/performance efímero del que únicamente quienes fueron testigxs del evento pueden dar cuenta. Neri vio a Bobby por primera vez en el invierno del 2023. Lo describe como un sujeto extraño que estaba en pleno frío, temblando y mostrando una pintura a los paseantes del parque al parecer sin objetivo alguno. Volvió a verlo unos meses después en el mismo lugar con otra pintura y no fue sino hasta la tercera vez que lo vio que se acercó a hablarle. Intercambiaron ideas y como resultado tomaron la decisión de hacer el gesto de que, la próxima vez, voltearían la pintura hacia una de las ventanas del MET desde la que se puede ver hacia afuera y viceversa. Para Neri, ése era el público más adecuado para la obra que estaba haciendo Haag. Este último se sintió incluso sorprendido de que alguien más compartiera la sensibilidad necesaria para apreciar su obra y accedió.

El MET es un museo de corte monumental donde la Historia del Arte es su eje principal, donde aquellas obras clásicas de la antigüedad van siendo clasificadas por culturas, regiones y tiempos hasta llegar al arte estadounidense como su último estadio. Con el hack propuesto con la obra de Bobby hay una serie de grados que se pueden rastrear y que nos dejan ver otros posibles. En un grado casi cero –asumiendo por supuesto la falta de origen– emerge la pregunta es si el artista ha de buscar entrar al MET o bien el espectador tiene que salir del museo para ver el arte, en lugar de quedarse en su esfera preparada para la experiencia estética. El gesto crítico actúa en ambos sentidos, como una infiltración pero también como una llamada hacia afuera. Y es que, como se ha dicho infinidad cantidad de veces, todo el arte dentro de un museo está muerto por el simple hecho de estar ahí. Y aunque pueda haber reacios ante esa postura, por lo menos tienen que admitir que esa especie de denuncia es un fantasma asecha a toda institución artística, y a veces les espanta mucho.

La pintura a mostrar en esta ocasión mide alrededor de 1.5 x 1 m. Se trata de un diente de león que Bob pintó con inspiración en lo que se puede encontrar afuera del MET, en Central Park. ¿Es el parque un adorno del museo o el museo un adorno del parque? No lo sabemos, pero si extendemos la pregunta a la ciudad del Central Park y luego de Nueva York al país al que pertenece, la ironía se nos sale de las manos. Haag está remarcando ya no sólo que el adentro y el afuera del museo puede ser retado, lo cual se ha hecho infinidad de veces en el arte del último siglo, cuando menos; lo que sale a la luz además de ello es que tanto adentro como afuera es una ficción muy real en la que vivimos y de la que somos parte todxs. Bobby ve algo en esa hierba que se considera una maleza regularmente. Él y toda persona que se atreva a ver al arte como algo que no está dentro del museo somos una maleza, eso lo sabemos. Y aún con eso no sufrimos lo suficiente como para no ver belleza entre nosotrxs. Jamás han logrado convencernos de ello y no lo lograrán. No pasarán. Por supuesto, ese intento del artista por mostrar la belleza que aún nos atrevemos a ver tiene que pasar por una operación existencial en la que todo lo que existe es bello por el simple hecho de atreverse a existir. Al llegar a este punto podemos decir entonces que este tipo de infiltración es lo que caracteriza al arte contemporáneo en sí. Ahí es cuando las fronteras entre adentro y afuera del museo no solo se quiebran, lo cual, repito, ya se ha hecho mucho, sino que las dos cosas y todo lo demás se eleva al nivel de apariencia. Ya no es nada más una crítica al mundo del arte o a la Historia del Arte, sino una asunción de que no tenemos de otra más que desearlo y desearlo en su forma originaria, aunque sepamos que no existe, jamás existió y no va a existir.

El hecho de que de pronto las pinturas de Bobby puedan parecer de Van Gogh, pero de pronto de algún expresionista abstracto estadounidense de mediados de siglo pasado, le conecta de manera singular. Este gesto puede ser de cualquier época al final. Pero para remitirme al término del libro que suscitó parte de esta acción, el arte anacrónico no se trata de retomar algún estilo anterior. Eso podría ser un gesto retro quizá. Pero la propuesta del anacronismo tiene más que ver con las posibilidades de mundo que puede abrir una obra, no porque se remonte mucho o poco a alguna otra época, sino porque simplemente eso no tiene peso frente a lo que provoca. No es que la obra de Haag represente una suerte de nueva tendencia en el arte, sino casi al contrario, muestra que siempre ha habido y va a seguir habiendo arte que no necesite de validación alguna para aparecer y hacerse ver. Frente a aquellas posturas que creen que el arte o el pensamiento sobre el arte, ya sea en forma de crítica, teoría o práctica contestataria, se decide en las políticas gubernamentales, que indudablemente le afectan, un caso como el de Bobby nos recuerda por lo menos dos cosas: 1) Que por más condiciones desfavorables que haya, y aunque incluso existan campañas para precarizarle, restringirle o controlarle, el arte insiste en abrir sus caminos propios. Más aún, su aniquilación total es imposible. Y 2) que, en el otro extremo, aunque haya las mejores condiciones materiales para apoyar a lxs artistas, el resultado de esa operación no forzosamente es buen arte. En medio de estos dos polos cabe un infinito. Cabe señalar que con esto no estoy diciendo que el arte de nuestro artista en cuestión sea bueno o malo, como tampoco que viva o no en condiciones adversas. Todo eso puede relativizarse en este caso. Lo que sí digo es que nos hace ver que tales posibilidades pueden existir.

En otro registro, es verdad que Bobby Haag es un artista estadounidense finalmente, ¿habría la posibilidad siquiera de que esto lo pudieran hacer inmigrantes ilegales o refugiadxs? Ésta es la historia no de una pieza ni de unx artista, ni de unx curador, ni de unx galerista ni mucho menos de unx académicx. Es la historia de un encuentro. El gesto crítico no le pertenece a nadie. Más que intentar defender que Haag es o no un artista del anacronismo, pues eso no me toca a mí, veo la acción como una forma de jamming y es por eso que me interesa. No sólo porque he escrito más de una tesis sobre ello, sino en primer lugar porque participar de este tipo de confluencias me fascina. Luego porque por supuesto me desbordan y tienen la capacidad de tocar a otrxs generando vínculos insospechados. Nos recuerdan que fuera de las redes del arte contemporáneo hay otro tipo de redes de apoyo mutuo que no forzosamente pretenden figurar ni pertenecer de esas esferas, que no se identifican, o que en todo caso las utilizan a favor de fuerzas que van más allá de ellas. Es otro tipo de arte contemporáneo en el sentido de que efectivamente responde a nuestro tiempo, pero incluso diría que se adelanta a otro tiempo, abriendo caminos hacia paradigmas más allá del capitalismo y los Estados nación, atravesando fronteras y límites de todo tipo, tal como lo hacen por ejemplo el lumbung o el Holograma. No es entonces arte contemporáneo pero tampoco es un arte del futuro, pues éste ya se encuentra secuestrado por los pensamientos que con rigurosidad pretenden especular hasta obtener el resultado más óptimo. En todo caso podría ser un arte del porvenir.

París, 9 de noviembre de 2024

Bobby Haag at the MET

Criticism: a necessary gesture, always urgent, to be constantly renewed. It is a way to look better at what we see, to know better our own desires, to rise up against what, as people say, “we have had it up to the eyeballs”. And to better imagine the emancipatory possibilities of the times to come.

Georges Didi-Huberman

I met Ignacio Neri in the context of the organization of the event Imaginación política: encuentro internacional, held in February 2017 at the MUAC. He supported us paying for the English-Spanish translation and vice versa, for the whole event. I stopped seeing him until the presentation of the book Adiós al arte contemporáneo, ¡viva el arte anacrónico! at Biquini Wax. He bought the book (insisting on paying for it) and a few weeks later contacted me to tell me how inspiring he found it. I would have never imagined it. Recently he wrote me again to tell me about a plot he has come up with together with artist Bobby Haag to take place on Saturday, November 9 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York. In this text I will tell a little bit about this confabulation brought about by unimaginable connections.

Neri, originally from Tulancingo, Hidalgo, studied at ITAM and later began collecting and promoting artists from self-organized spaces as a gallerist, supporting collectives like Biquini Wax and Cráter invertido, among others. Three years ago, he moved to New York to study a MA in Climate and Society at Columbia University. Since then he has been living and working in that city. He tells me that he has visited many art exhibitions and events and that he is sure that better art is produced in Mexico City than in New York. Without being able to explain exactly why, we share an idea – deeply felt and committedly romanticized – that for some reason adverse contexts and times of danger incite creativity, or at least that’s how it is experienced when you are there.

For his part, Haag is an artist who has been painting in oils since he was 20 years old. He painted for a whole decade alone and to himself, without showing his paintings to the public. Then in May 2022 he moved to New York, to Brooklyn, in Bushwick, a neighborhood that is in the process of gentrification. The first painting he did in that city was a portrait of the person who told him “follow your dreams.” That painting is particularly interesting because unlike some of his other works, in that picture there is a large amount of mixed colors configuring textures that at times seem to be totally random and at other times seem to be perfectly calculated. In this work Bobby seems to deposit all his affections for this character, turning him into something fictional, like an ethereal being that, in any case, probably has more to do with his own way of responding to this suggestion than with the subject himself.

During his stay as a New Yorker, he began to work as part of the technical team of Christie’s auction house. But at the same time he began to paint the things he saw in Central Park, near the MET, where he found a series of scenes that inspired him to paint them in oil. From there he decided to exhibit one of those paintings right there in the park for a whole day, from 6am to 6pm, selected to be shown only once for each season of the year, that is to say, once every 3 months approximately. It is worth mentioning this anachronism that can take us back to those nineteenth-century gestures of the attempt to escape from the urban imagery to let oneself be overwhelmed by what at that time was still idealized as “nature”, as well as to motifs of even more classical inspiration that can be found in a great number of paintings, sculptures, music, etc.

From August 9 to 15 of this year, Haag had the opportunity to participate in the exhibition and auction “Christie’s Inside Job”, organized by the renowned company that as a token of generosity allows some of its workers. There he made his first and only sale of work so until now. In the meantime, they continued their activity in the park. Bobby’s paintings are generally rather crude. And he himself admits his lack of technical mastery. He says: “the only reason it looks like anything that has been done before is because I’m not a master”. Dissimilar and at times vibrant colors are mixed to such a degree that they generate both tactile and visual textures. We cannot say, and he certainly could not prove it himself, to what extent this effect is voluntary. At times his stroke seems so childish that it could well be the result of an effort to remain naïve. Only the conscience police would go after such an inquiry. If this is unimportant, it is not only because the act of painting itself has already been overexploited by the circuits of the supposed knowledge about art, but also because, although it continues and will continue to be a pretext to turn to any surface and become an image, the critical gesture is not only there. It is in what we do with it.

For Neri, Haag’s art reminds him of Henri Rousseau’s, especially in terms of the workmanship and self-taught mode. But at the same time, Neri also saw in him something of David Hammons, in the sense of going out into the street and making an ephemeral exhibition/performance that only those who witnessed the event can account for. Neri first saw Bobby in the winter of 2023. She describes him as a strange fellow who was out in the cold, shivering and showing a painting to passersby in the park seemingly without purpose. She saw him again a few months later in the same place with another painting and it wasn’t until the third time she saw him that she approached him to talk to him. They exchanged ideas and as a result made the decision to make the gesture that, next time, they would turn the painting towards one of the windows of the MET from which you can see out and vice versa. For Neri, that was the most appropriate audience for the work Haag was doing. The latter even felt surprised that someone else shared the sensitivity necessary to appreciate his work and agreed.

The MET is a monumental museum where the History of Art is its main axis, where those classical works of antiquity are classified by cultures, regions and times until reaching American art as its last stage. With the hack proposed with Bobby’s work, there are a series of degrees that can be traced and that allow us to see other possible ones. To an almost zero degree -assuming of course the lack of origin- the question emerges as to whether the artist must seek to enter the MET or whether the viewer must leave the museum to see the art, rather than remain in its sphere primed for aesthetic experience. The critical gesture acts in both senses, as an infiltration but also as an outward call. And the fact is that, as has been said countless times, all art inside a museum is dead by the simple fact of being there. And although there may be reluctance to this position, at least they have to admit that this kind of denunciation is a ghost that haunts every art institution, and sometimes it scares the hell out of them.

The painting to be shown on this occasion measures about 1.5 x 1 m. It is a dandelion that Bob painted with inspiration from what can be found outside the MET in Central Park. It is a dandelion that Bob painted with inspiration from what can be found outside the MET, in Central Park. Is the park an ornament of the museum or the museum an ornament of the park? We don’t know, but if we extend the question to the city of Central Park and then from New York to the country to which it belongs, the irony gets out of hand. Haag is not only remarking that the inside and outside of the museum can be challenged, which has been done countless times in the art of the last century at least; what also comes to light is that both inside and outside is a very real fiction in which we live and of which we are all a part. Bobby sees something in that herb which is regularly considered a weed. He and anyone who dares to see art as something that is not inside the museum are weeds, we know that. And yet we don’t suffer enough not to see beauty among us. They have never managed to convince us of that and they will not succeed. No pasarán. Of course, this attempt of the artist to show the beauty that we still dare to see has to go through an existential operation in which everything that exists is beautiful for the simple fact of daring to exist. At this point we can say then that this type of infiltration is what characterizes contemporary art itself. That is when the boundaries between inside and outside the museum not only break down, which, I repeat, has already been done a lot, but both and everything else is elevated to the level of appearance. It is no longer just a critique of the art world or Art History, but an assumption that we have no choice but to desire it and desire it in its original form, even though we know it does not exist, has never existed and will never exist.

The fact that Bobby’s paintings can suddenly look like Van Gogh, but suddenly like some mid-century American abstract expressionist, connects him in a unique way. This gesture could be from any era in the end. But to refer back to the term in the book that prompted part of this action, anachronistic art is not about revisiting some earlier style. That could be a retro gesture perhaps. But the proposal of anachronism has more to do with the possibilities of the world that a work can open up, not because it harkens back too far or too little to some other era, but because it simply doesn’t matter in front of what it provokes. It is not that Haag’s work represents a sort of new trend in art, but almost the opposite, it shows that there has always been and will continue to be art that does not need any validation to appear and be seen. As opposed to those positions that believe that art or thinking about art, whether in the form of criticism, theory or contestatory practice, is decided by government policies, which undoubtedly affect it, a case like Bobby’s reminds us of at least two things: 1) That no matter how unfavorable conditions may be, and even if there are campaigns to make it precarious, restrict or control it, art insists on opening its own paths. Moreover, its total annihilation is impossible. And 2) that, at the other extreme, even if there are the best material conditions to support artists, the result of this operation is not necessarily good art. In between these two poles there is an infinity. It should be noted that with this I am not saying that the art of our artist in question is good or bad, nor that he lives or does not live in adverse conditions. All that can be relativized in this case. What I am saying is that it makes us see that such possibilities can exist.

In another note, it is true that Bobby Haag is an American artist finally, would there even be the possibility that this could be done by illegal immigrants or refugees? This is the story not of a piece, not of an artist, not of a curator, not of a gallerist, and certainly not of an academic. It is the story of an encounter. The critical gesture belongs to no one. Rather than trying to defend that Haag is or is not an artist of anachronism, since that is not up to me, I see the action as a form of jamming and that is why I am interested in it. Not only because I have written more than one thesis about it, but first of all because participating in this kind of confluences fascinates me. Then, of course, because they surpass me and have the capacity to touch others, generating unsuspected links. They remind us that outside the networks of contemporary art there are other kinds of networks of mutual support that do not necessarily pretend to figure or belong to those spheres, that do not identify themselves, or that in any case use them in favor of forces that go beyond them. It is another type of contemporary art in the sense that it effectively responds to our time, but I would even say that it anticipates another time, opening paths towards paradigms beyond capitalism and nation states, crossing borders and limits of all kinds, much like, for example, lumbung or Hologram do. It is not contemporary art then, but neither is it an art of the future, since it is already kidnapped by thoughts that rigorously pretend to speculate until the most optimal result is obtained. In any case, it could be an art of the unpredictable time to come.

Paris, November 9, 2024

1 comentario en “Bobby Haag @ MET, nov. 9, 2024”